Growing Food, Generating Energy

We need food. And we need clean energy.

But in Oregon, and elsewhere, solar and agriculture are starting to compete for the same land. Do we have to choose between harvesting crops and harvesting the sun? We don’t think so. It turns out that combining solar panels and growing crops in the same field, or Agrivoltaics, may actually benefit both. The cooling effect of growing plants means solar panels generate more electricity and last longer. And the higher soil moisture levels and cooler temperatures under solar panels mean less water is needed for irrigation, healthier, less stressed animals and plants.

Solar Harvest

What’s missing is the research demonstrating how they can work together best. Which is why Oregon Clean Power and OSU’s College of Agriculture teamed up to build Solar Harvest, the first field-scale research station specifically designed to allow researchers to study the impact of solar panels on soil health, water use, and plant physiology and yields.

The project started construction at the end of September 2022, and started producing power in April 2023. It is fully subscribed, but if you’re interested in getting power from future projects, please fill out the form here.

Participants in Solar Harvest get their power from the sun, while helping advancing the research we need to understand how solar and farming can coexist, leading us to a future where we all have enough to eat, and clean power from the sun.

But don’t plants need full sun?

Most plants don’t actually need all the sunshine that’s available to them to grow well. Researchers have successfully grown aloe vera, tomatoes, corn and lettuce in the intermittent shade cast by PV panels. Some varieties of lettuce even produce greater yields under PV panels than in full sunlight.

Lettuce alone could justify a national project in agrivoltaics. In 2012, U.S. farmers grew lettuce on 267,100 acres. PV panels on that land could generate 77 GW of electricity, more than the total U.S. installed capacity (60 GW) of PV power in 2018. Research by Prof. Chad Higgins, Solar Harvest Principal Investigator, shows that converting just 1% of the world’s agricultural land to agrivoltaics would offset global energy demand.

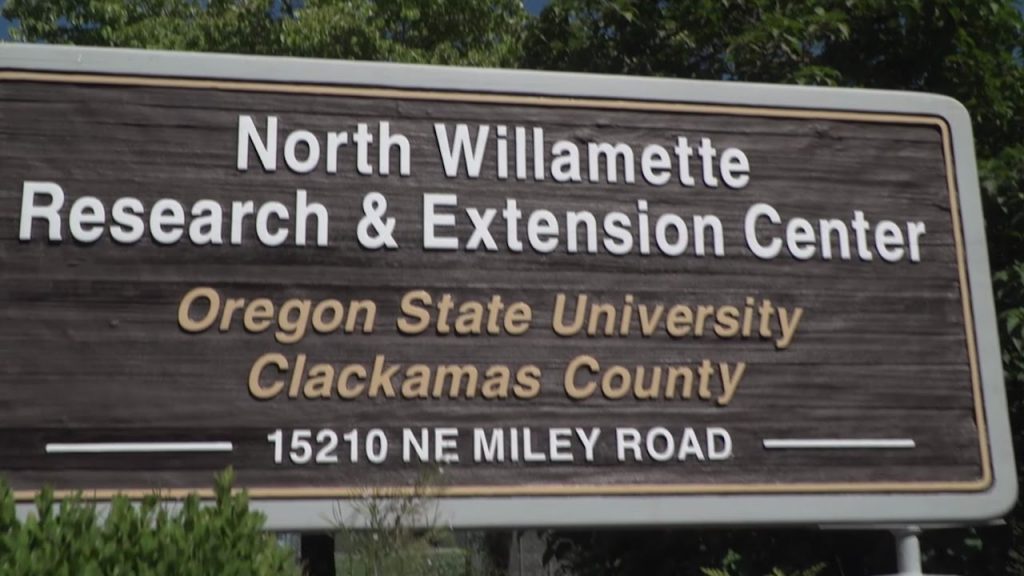

Solar Harvest is located on a six-acre field in the center of OSU’s North Willamette Research and Extension Center (NWREC), a 160-acre farm in Aurora, Oregon. The soils at the NWREC are among the most productive in the country, and are suitable for a wide range of crops. OSU’s research will focus on plants with a high net photosynthetic rate, and shade-tolerant crops, which include alfalfa, arugula, beets, bok choy, cabbage, carrots, chard, garlic, onions, parsley, radish, spinach, sweet potato, turnips, and yams.

Solar Harvest was funded with the assistance of: